As the seemingly interminable sequence of adverts began, I was aware of being almost alone in the cinema. Apart from myself and a friend, there were only three or four others settling into their plush theatre seats.

The film was a German one called ’13 Minutes’, subtitled for English-speaking audiences, and told the little-known story of an attempted assassination of Hitler in November 1939.

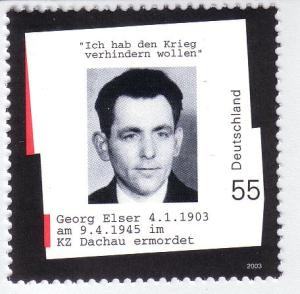

A German commemorative postal stamp from 2003: “I wanted to prevent the war”. Elser was murdered on 9th April 1945 in Dachau concentration camp.

Georg Elser, a young man from a rural village, becomes increasingly disturbed by the way Germany is changing under the Nazis. By the late 1930s, having seen a friend arrested and sent to a concentration camp and a local woman persecuted for her relationship with a Jewish man, he is convinced that he must try to kill Hitler. He makes a bomb and plants it in a beer hall in Munich where Hitler is due to speak. The device explodes thirteen minutes after Hitler has left the building, killing eight innocent people. Elser is arrested that same evening, questioned, tortured and sent to a concentration camp where he is killed in the final weeks of the war.

Reviews in Britain and Germany have been varied, but something on which everyone agrees is Elser’s astonishing absence from history. It is not only British faces that remain blank when his name is mentioned – the German actor who plays Georg admits never having heard of him before reading the script. Yet director Oliver Hirschbiegel has likened him to the controversial whistleblower Edward Snowden, whose name is unlikely to be forgotten in our lifetimes.

So why has Elser’s story lived in obscurity for so long? Hirschbiegel thinks his working-class background might be to blame. There was simply disbelief, among both the Nazis who arrested him and ordinary Germans, that such a man could have planned and carried out the attempt without help.

I wonder if it was due to his lack of affiliations. He was vocally anti-communist, even apolitical, so there was no obvious group to tell his story and fight for his recognition after the war.

But most importantly, Elser was a victim of a world where the villains receive far more attention than the heroes. Films such as ’13 Minutes’ and ‘Schindler’s List’ are vastly outnumbered by those that gratify our obsessive desire for cinematic displays of terror from Hitler and the Nazi high command. All too often, the heroes go unnoticed.

And this doesn’t just apply to the Second World War. It is villains not heroes that tend to fill column inches, cause twitter sensations and fill cinemas.

The global public is outraged when a lion is killed illegally for pleasure, but neglects the wonderful, heroic work being done every day to preserve our planet’s species. We vilify the Calais authorities for failing to control migration, but ignore the local volunteers running French lessons in the migrant camps and the British individuals fostering Eritrean children.

We should hunt out and recognise the heroes in our midst, even if, like Elser, they fall short of their ambitious targets. Let’s give less credence to the villains and write about the heroes instead.